From the mountains to the oceans: the path of sediments transported by the Amazon rivers

3 March 2021 | Duration of reading: 6 min

By Hugo Fagundes

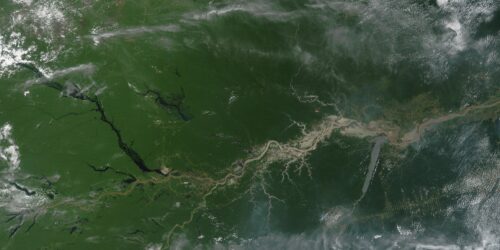

Understanding the sediments (rock fragments that compose the soil) transport path is important for many reasons. Some of these reasons are the understanding of the relationship between sediments and agricultural productivity, the maintenance of several species and ecosystems, the decrease of reservoirs life span (such as hydroelectric power plants) and the aggradation of rivers. South America is among the world regions with highest sediment transport, in which the Amazon River is responsible for 44% of its sediment contribution to the oceans. As previously presented in a text by Alice Fassoni-Andrade (Mapping river and lake sediments of the Amazon plains from space), sediments available in this river and in its tributaries are essential for fauna and flora species distribution and richness, and also for soil fertility of Amazon floodplains.

Monthly suspended sediment discharge (QSS) in South America rivers in tons per day. The color scale presents values in a base-10 logarithmic scale, that is, 10 to the scale values power. Source: Fagundes et al., 2021

So, how do sediments get out of the mountains and reach the oceans? It all starts when it rains. The rain will detach the soil particle and from there, the water flowing on the slopes will transport these sediment particles to the nearest water body, which may be a river that will find another river. Then, the water will carry the particle until it reaches the oceans (or it will be deposited along the way, as we will see further).

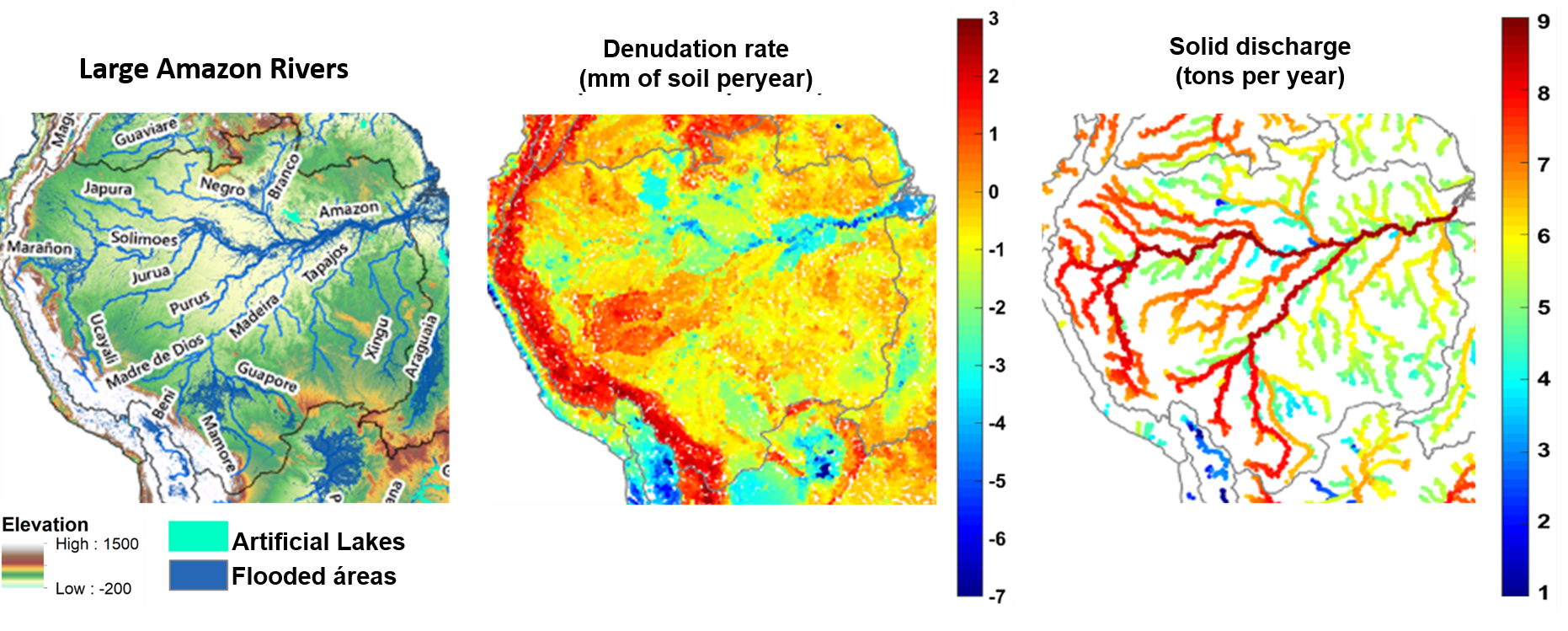

Largest Amazon rivers; denudation rate: time in which the topsoil layer decreases; and solid discharge: amount of sediment transported by a river reach in a given period. Source: Fagundes et al., 2021

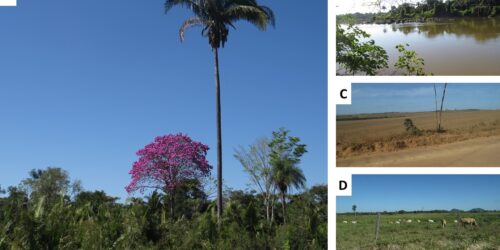

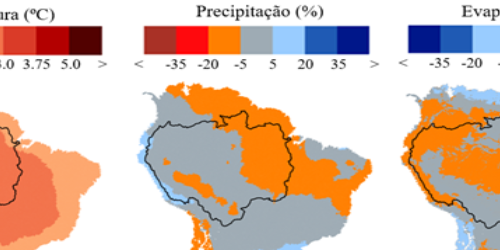

The Andean region (a mountain chain in the South America western region) has the highest rate of soil denudation (time in which the topsoil layer decreases). This makes this region the main sediment source for the Amazon rivers; we can call it the yield zone. The lowest slope areas (dark green) are primarily responsible for sediment transport; we can call them transport zones. The flatter regions (light green) and the flooded areas are those where most of the sediment deposition occurs; we can call them deposition zones.

The Solimões River and the Madeira River are the main sediment transporters. About 50% of the sediment delivered to the Amazon River outlet comes from the Madeira River. The Negro River (a river of black waters) has a high water discharge and transports less sediment than smaller rivers, such as the Japurá, Purus and Juruá rivers. The Tapajós and Xingu rivers have clear water and, thus, also transport low amounts of sediment.

Most of the suspended sediments are trapped in the Amazon floodplains. In the following figure we identified some of the major Amazon floodplains with yellow dots. The suspended sediment concentration in rivers generally decreases after the floodplains, having major implications in the maintenance and dynamics of local ecosystems. The floodplains that retain most sediment are located close to the Andes and in the Central Amazon, after the confluence of the Negro and Solimões rivers. In addition, as river water discharge increases the sediments concentration tends to decrease due to sediment dilution.

Annual average suspended sediment amount deposited in the major Amazon floodplains. The color of the rivers indicates the daily average concentration of suspended sediments (CSS) in its reach. The thickness of the rivers indicates the river discharge (Q).

Thus, the sediment path from the mountains to the oceans is long, and not all of them reaches the coast. Along this path, sediments are an important “food” for rivers and help to maintain ecosystems. Therefore, in future works, we intend to assess the impacts of human action and climate change on sediment transport.

Science is done collaboratively

The results presented in this text were obtained from the paperSediment flows in South America supported by daily hydrologic‐hydrodynamic modeling” published in the journal Water Resources Research in 2021 (see list of materials below). These results are part of the research carried out by Hugo de Oliveira Fagundes during the Ph.D in the Postgraduate Program in Water Resources and Environmental Sanitation at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, under the guidance of professors Fernando Fan and Rodrigo Paiva. This research had the financial support of the Brazilian federal government through a CNPq.

Want to know more? Access the links below!

Fagundes, H. D. O., Fan, F. M., Paiva, R. C. D., Siqueira, V. A., Buarque, D. C., Kornowski, L. W., … & Collischonn, W. (2021). Sediment flows in South America supported by daily hydrologic‐hydrodynamic modeling. Water Resources Research, 57(2), e2020WR027884. (Link)

Fassoni-Andrade, A. C. & Paiva, R. (2019). “Mapping spatial-temporal sediment dynamics of river-floodplains in the Amazon.” Remote Sensing of Environment, 221: 94-107. (Link)

Filizola, N., Guyot, J.-L., Wittmann, H., Martinez, J.-M., de, E., (2011). The Significance of Suspended Sediment Transport Determination on the Amazonian Hydrological Scenario. Sediment Transp. Aquat. Environ. (Link)

Filizola, N., Guyot, J.L., 2011. Fluxo de sedimentos em suspensão nos rios da Amazônia. Rev. Bras. Geociências 41, 566–576. (Link)

Latrubesse, E.M., Stevauc, J.C., Sinha, R., 2005. Tropical rivers. Geomorphology 70, 187–206. (Link)

Hugo is Environmental Engineer (UFES) and Master in Water Resources and Environmental Sanitation (UFRGS). More information on Large Scale Hydrology Group, Plataforma Lattes, ResearchGate and LinkedIn.